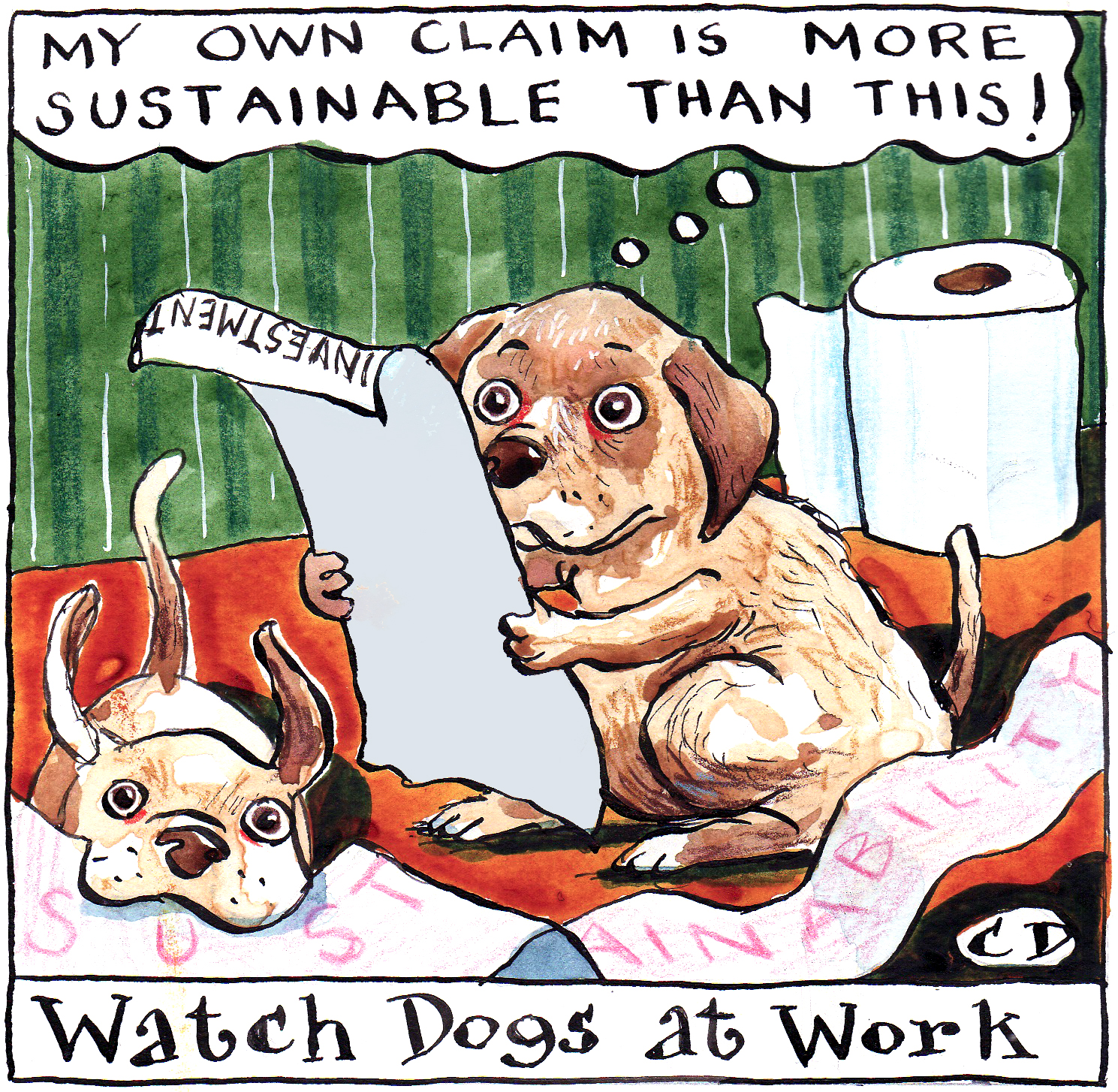

Stopping funds greenwashing makes sense … but is it sustainable?

One of the plagues of modern life is the specious claim of sustainability. Everything is sustainable. There is the Sustainable Coal Stewardship, a programme run by FutureCoal, a coalmining trade body. There is sustainable aviation fuel (Virgin Atlantic was recently schooled by the Advertising Standards Authority for making over-excited claims about the fuel’s environmental credentials). And, of course, some Japanese marine scientists are promoting the idea of sustainable whaling, which I suppose could actually be a thing.

Sustainability is now merely a marketing term. When everything is sustainable, then nothing is. It is a particular problem when it comes to working out how to invest your money. You can apply a quick commonsense test to some sustainability claims (“does this brand of toilet paper really make puppies gambol about?”), but working out the difference between one fund manager’s environmental credentials and another’s is something else. Even the most committed of green investors will struggle to work out exactly where a fund has invested and even fewer will go through the thought process that guides the manager’s choices.

You can argue for hours, for example, about whether owning shares in BP and Shell is compatible with a sustainable investment approach. Some will say that we will be using oil and gas for the foreseeable future and that these are the companies with the money to invest in new types of energy. You should own the shares in order to push them faster in that direction. Others will argue that this is wishful thinking. Fossil fuels are bad, so don’t give them your money.

The watchdog that polices investment funds in Britain is trying to bring some order to the chaos. Two years ago I wrote about the Financial Conduct Authority’s plan to stop greenwashing by funds. It was a simple scheme: funds would have to stop throwing around green investment buzzwords such as “sustainable” and “impact”; they would be able to use them only as part of three specific labels and would have to prove to the FCA that their funds met the rules set down for each.

The consultation has been long and reasonably contentious, but the rubber has finally hit the road. There are now four labels and, since July 31, funds have been able to notify the watchdog that they intend to use them. There is a grace period until December 2 while they work out what they want to do, but after that “sustainable”, “sustainability” and “impact” are forbidden unless you have gone through the process and are using the labels.

How is it going? “Slowly,” would seem to be the answer. I have badgered the FCA for the past ten days for the number of funds that have given notice. While I got lengthy responses about the basics of the scheme and its aims, the closest I got to a number was “a handful”. Others I have spoken to about the chats between the watchdog and some funds considering applications say the actual number is six.

It’s not hard to work out why fund managers are taking their time. The rules are challenging and working out which label should apply, and how you will prove you qualify, will take some effort.

The first is Sustainability Focus, for funds that invest at least 70 per cent of their money in assets that are “environmentally and/or socially sustainable”. Yet you can’t simply say you are doing it. You have to prove it using a “robust, evidence-based standard that is an absolute measure of sustainability”, a test that naturally will open up another set of questions about exactly which measures are suitable.

Second is Sustainability Improvers, for funds with 70 per cent of assets that have “the potential to improve environmental and/or social sustainability over time”. Again, firms must produce “robust evidence” to back up their claims.

Third is Sustainability Impact, for those that “aim to achieve a pre-defined positive, measurable impact in relation to an environmental and/or social outcome”. Again, there needs to be some proof, but also firms must specify “a theory of change”, a requirement that might provide some lucrative consultancy work for philosophers.

The last one is Sustainability Mixed, a broader class that was introduced to try to meet the needs of some multi-asset funds. Multi-asset is a popular style of fund management. The idea is that you combine a bit of everything, shares, bonds, currencies and alternative investments, in an effort to smooth out returns. The Mixed label allows you to invest 70 per cent of the assets “in accordance with a combination of the sustainability objectives for the other labels” and you have to meet the tests for each.

All this must be pretty brain-shredding for managers who have been slapping “sustainable” on their funds for the past decade without much thought, apart from how it might justify higher fees. Getting right into the nitty-gritty and providing solid proof that what you are doing will help the environment or society will take all the fun out of it.

You could be naughty. You could use the labels anyway and hope to get away with it. The FCA says that when a firm adopts one, it “remains responsible for its classification and ensuring the label is appropriate”. But the regulator will be keeping an eye out. “We will respond to compliance issues when they arise and act if we have intelligence that indicates a firm may not be meeting the requirements.”

If you were thinking of just winging it and using the three forbidden words without the label, beware. They, or any variation of them, “must not be used” and, if they are, you can justify it only by producing “the same types of disclosures as required for a labelled product”.

It’s too soon to say how all this will work out. If the FCA has set the bar too high, the number of environmental funds will shrink dramatically. That could be very good news for those that are able to use the labels because a survey of savers that the watchdog undertook in support of its work found that 80 per cent of people wanted their savings to do good as well as to earn a return. Those green funds still standing could enjoy a big influx of money.

I suspect that in the end there may not be a drastic winnowing. Managers will be loath to cut themselves off from a big section of the market and will fall into line with what the FCA wants, even if it proves expensive. Given the glacial pace of progress so far, however, expect a logjam of applications at the end of the year.

Dominic O’Connell is business presenter for Times Radio

Post Comment